The AI revolution has elevated computing power into one of the world’s most coveted resources, yet its market remains immature and volatile. GPU rental prices can swing wildly amid drastic supply-demand imbalances (from under $1 to over $8 per hour), there has historically been no way to hedge or stabilize costs, and pricing is largely determined in private deals rather than in a unified market structure. A new paradigm is emerging, however, one that treats compute as a tradable asset class, complete with exchanges, futures, and spot markets.

Compute isn’t like most tradeable assets, though, in one very important way: not all compute units are created equal. A top-of-the-line NVIDIA H100 GPU hour isn’t perfectly interchangeable with an older GPU or a CPU hour - yet they are not completely unique either. Compute occupies a middle ground on the spectrum of fungibility, and is what we would call a semi-fungible asset.

As crypto enables markets to emerge for everything (from predictions to memes), we expect that the design space for these semi-fungible assets will be a particularly interesting one. So let’s take a quick look at what semi-fungible assets are, how they could be applied to compute markets in particular, and where we believe the world may be going as agents begin consuming compute on our behalf.

What Does “Semi-Fungible” Mean?

In traditional finance, an asset is fungible if any two units are indistinguishable (e.g. any two shares of the same stock are identical) and non-fungible if each unit is unique (like a work of art or a specific real estate property). Semi-fungible assets lie in between - they are similar but not exactly identical. Often they can be partially ordered by quality or preference: some are better than others, some worse, and some simply different. In other words, you can group them by classes or grades, but there are still multiple distinguishable varieties within an asset category. A buyer may consider several items interchangeable if they meet certain criteria, but might pay a premium for a higher-grade variant.

Real-world markets are full of semi-fungible assets. A few examples include:

- Bonds: Bonds come in many issuances with different maturities and credit ratings. Traders treat bonds with the same rating and yield as roughly equivalent, even if issued by different entities.

- Commodities: Metals like gold are graded by purity and delivery location. An ounce of 99.99% pure gold in London is equivalent to an ounce of the same purity in New York, but gold of lower purity (or in a different form) trades at a discount.

- Crypto Tokens: In crypto markets, liquid staking tokens or vault tokens vary by provider reputation and risk, though they all represent staked assets on a blockchain.

These items aren’t identical enough to lump into a single homogenous order book, yet they aren’t so unique that each requires its own siloed market. Semi-fungibility is the concept that captures this nuance.

The recent research paper “Market Clearing with Semi-Fungible Assets” by Diamandis, Chitra, and Angeris, formalizes how to price and trade such assets in a unified market. The key idea is to leverage a partial order over asset types. If one asset is strictly “better” (more preferred) than another along all relevant dimensions, it should command an equal or higher price. But assets that differ in incomparable ways (for example, one bond has higher yield but lower credit rating than another) might trade simultaneously at different price points without a simple overall ranking by price. By structuring the market around a partial order of asset properties, buyers can express flexible preferences (“I’ll accept anything at least as good as X”) while supply and demand are still aggregated efficiently. The result is a market that not only clears (matching all buyers and sellers), but also maximizes total surplus across participants - something that wouldn’t be possible if each slightly different asset was confined to its own independent market.

Compute as a Semi-Fungible Asset Class

Compute resources are a textbook example of semi-fungible assets. When you purchase cloud computing or GPU time, you’re ultimately buying a certain amount of computational work (FLOPs, memory, IO) for a time period. But there are many ways to get those FLOPs. For instance, training a machine learning model on the latest GPU (say an NVIDIA H100) might get the job done fastest; using an older GPU (like an A100 or V100) could be slower but perhaps cheaper; using a large CPU cluster or even a custom TPU could be alternatives with different performance-cost tradeoffs. From the buyer’s perspective, these options are neither completely fungible nor entirely distinct - they have a partial order in terms of performance and preference. A buyer might insist on at least a certain level of GPU capability, but beyond a point, faster is just “nice to have” rather than strictly necessary. Other dimensions come into play too: one GPU provider might be more trusted or reliable than another, or a cloud region might be preferred for latency reasons. All these properties create a lattice of possible compute resources. Ultimately, however, they are all providing the same basic good - computing cycles - just with different qualities and speeds. “All buyers are purchasing FLOPs for some time period,” as the paper notes, even if they care about how and where those FLOPs are produced.

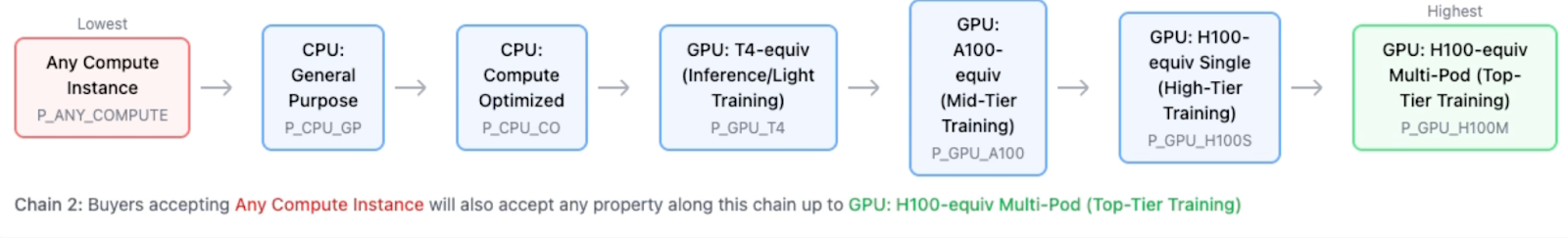

Diagram: Property Partial Ordering

A semi-fungible market framework is well-suited to handle these nuances in compute markets. It allows us to treat “compute” as a single broad commodity with gradations. Instead of fragmenting the market into countless instance types and provider-specific offerings, buyers and sellers could converge in one clearing mechanism where, say, H100 GPU-hours, A100 GPU-hours, and CPU-hours all clear together with appropriate price differences. The market-clearing algorithm we’ve been developing finds equilibrium prices such that supply meets demand across these categories simultaneously, and no one can profit by shifting to a different tier of resource. Intuitively, the price of each compute tier ends up set by the highest value use-case that can utilize that tier. For example, if any buyer is willing to pay up to $X/hour for an A100 (perhaps someone who doesn’t need an H100’s full power), then the price of A100 time will settle at $X (unless supply is so abundant that even that buyer’s demand is satisfied cheaper). A superior resource like an H100, which all A100 buyers would also happily use if prices were equal, will never end up cheaper than the A100 - there will always be demand to arbitrage away a price inversion. This kind of unified pricing is impossible in a traditional siloed market but emerges naturally in a semi-fungible exchange.

Demo: Clearing a Semi-Fungible Compute Market

To make this concrete, we built a prototype application that demonstrates market clearing with semi-fungible compute assets.

In our demo, a set of buyers submit their workloads with preferences, and a set of providers offer different hardware capacities. The system then computes the allocation and prices that clear the market - using convex optimization “under the hood” to maximize total utility subject to supply constraint. The result is a set of prices for each resource tier and an assignment of who gets what hardware, in a way that no one can improve their outcome by bidding differently.

This demo showcases a few important features in action:

- Group Buying and Selling: Buyers who are effectively competing for the same H100 resource pool end up grouped together. For example, buyer A’s higher willingness to pay sets the H100 price, and buyer B will only get H100s if the price falls within his budget.

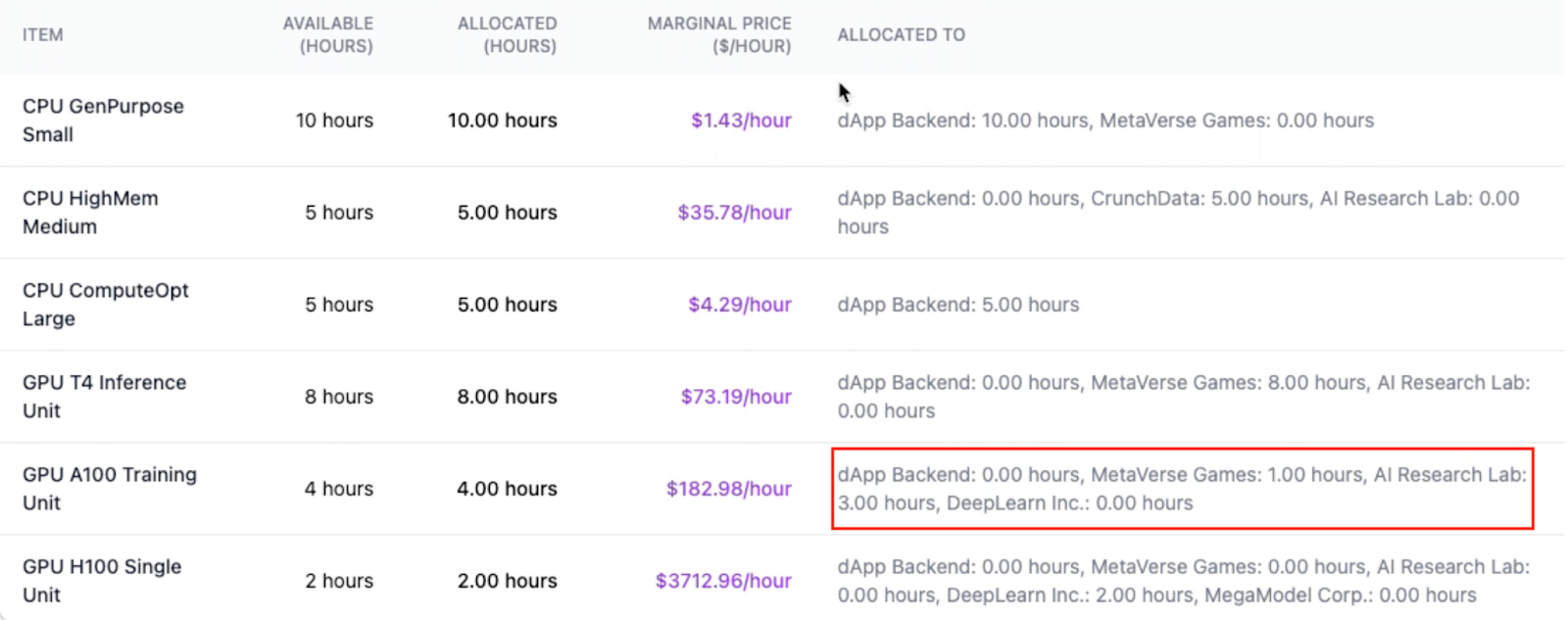

- Substitution: Buyer B seamlessly shifts to a lower tier GPU (e.g. A100) once H100s become too expensive, because the mechanism understands buyer B’s relative utility for H100 vs. A100 and will allocate the cheaper resource if it satisfies their needs. In a run of our model (shown below), MetaVerse Games is allocated 1 hour of A100 GPU capacity despite only asking for a cheaper T4 upfront. While the AI Research Lab took 3 of the A100 hours by request, the remaining 1 hour of A100 capacity meant MetaVerse Games was automatically upgraded, given the logic that their utility for higher value compute is strictly better than their baseline utility. This demonstrates the substitutive power of semi-fungible partial ordering.

Diagram: Item Allocation Breakdown By Entity

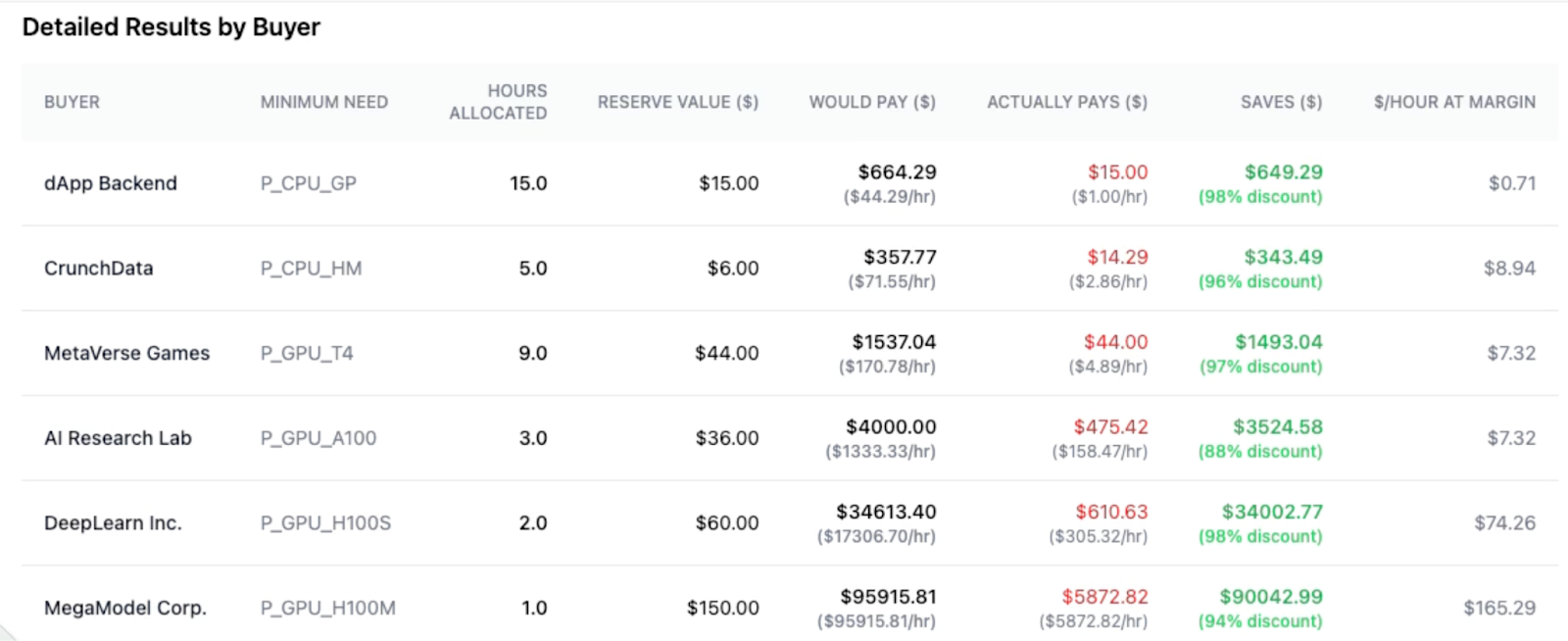

- Efficient Clearing: No GPU sits idle if there’s a lower-priority user willing to pay the clearing price for it. If buyer A only needed, say, 50% of the H100 supply, the rest could be allocated to buyer B at a slightly lower price point - yet still higher than the A100 price - until supply and demand balance out. This kind of multi-tier, multi-party matching all happens in one unified auction, rather than via ad-hoc pricing rules or manual market making. As an example of this in action, our model run shown below illustrates the utility savings for each entity due to the market clearing mechanism respecting their preferences, allocating resources according to these preferences, and optimally substituting strictly better tiers of the semi-fungible asset (compute) wherever possible.

Diagram: Optimal Market Clearing Results

From a user perspective, this experience can be quite simple: you submit a job request with your minimum acceptable hardware (and perhaps a value or bid curve indicating how much faster hardware benefits you), and the market returns an allocated slot and a price. No need to manually shop across providers or instance types - the mechanism does the work of finding you the best option at the best price. In traditional cloud terms, it’s as if there was a single “order book” for compute where an hour of an H100 in any compliant data center is one asset, an hour of an A100 is another, etc., and you just state what you’re willing to pay for the performance you need. Our prototype is a small step toward this vision.

The New Wave of Compute Marketplaces

While this market structure hasn’t yet been widely deployed, a growing set of platforms is working to commoditize compute and introduce liquidity into GPU markets.

For example, Ornn Exchange is building a U.S.-regulated derivatives exchange for GPU compute, SF Compute operates a real-time spot market for GPU rentals, and Compute Exchange is pursuing an auction-based marketplace with standardized contracts and real-time price discovery to unify GPU trading.

A key question is how this market structure could span both centralized hyperscalers and decentralized compute networks. Today, the Big Three cloud providers dominate through reliability and convenience, but at high cost and with significant vendor lock-in. In contrast, decentralized compute networks like Render and Akash have emerged. These platforms are attempting to build peer-to-peer GPU marketplaces via blockchain, matching those who need compute with those who have horsepower to spare. These decentralized platforms compete on price and openness, but face challenges around reliability, trust, and ease of use relative to centralized players, and thus have struggled to date to achieve utilization at scale.

Semi-fungible asset markets could serve as a unifying layer between centralized and decentralized supply. In a partial-order model, you can incorporate resources of varying trust and performance under one roof. For instance, one dimension of the partial order could be provider reliability/security. A server hosted in a Tier-4 data center with strict SLAs (typical of AWS) might be considered “higher grade” than a GPU rig in someone’s garage on Akash, even if the hardware is similar. Some buyers might be fine with the latter if it’s cheaper, whereas others might insist on the former. In a semi-fungible exchange, both types of resources can be listed - say as separate asset classes (e.g. “Verified GPU-hour” vs “Unverified GPU-hour”) or even graded continuously by a reputation score. The market will price each according to demand. The result is that, rather than a yes/no choice between completely separate ecosystems, buyers could dynamically choose based on price: e.g. a flexible workload might go to whichever provider is cheapest at the moment, whereas a mission-critical workload pays extra for a top-tier provider.

A Glimpse of the Future: Autonomous Compute Consumption

Where is all this heading in the coming years? One provocative idea is that in the future, we will all have intelligent agents that manage our compute needs automatically. Instead of manually renting servers or clicking buttons on a cloud console, you could entrust an AI agent with your utility function (your preferences for speed vs cost vs reliability) and let it procure compute for you in the most efficient way. This agent would continuously monitor the compute market - which could vary in real-time like a stock market - and it would schedule or execute tasks when conditions are most favorable.

For example, suppose you have a personal AI that retrains some models on your data, does backups, or renders some videos for you. You don’t particularly care if those jobs run at 2am or 2pm, as long as they finish by the time you wake up. Your agent could observe that GPU prices tend to dip in the early morning hours (perhaps because overall demand is lower then) and thus schedule the bulk of its work for those off-peak times, saving you money. If the agent sees a sudden spot opportunity - say a provider dumping excess capacity at a 50% discount - it could grab it and do some extra processing that it knows you’ll benefit from. Essentially, it’s automated bargain hunting for compute.

Cloud providers already offer rudimentary versions of this (AWS Spot Instances give you cheaper rates if you’re willing to be pre-empted, and some folks schedule workloads at night to exploit lower cloud prices), but an AI agent in an open market could take it to the next level, acting across multiple platforms and reacting to live price signals. In an exchange like SFC or Compute Exchange, it could place limit orders like a trader: “Buy 100 GPU-hours if price falls below $1.00 within the next 24 hours” - and if that order fills at 3am, the agent wakes up some containers and gets the job done by 5am. All while you’re asleep, and you pay perhaps 30% of what you would have during peak hours. Your agent could even anticipate your future needs (maybe it knows you’ll do a big data analysis next week) and pre-purchase cheap compute credits or futures when prices are low, then use them when you actually need them. This is analogous to an energy management system that buys extra power when rates are low and stores it (or in this case, does flexible work ahead of time).

From the enterprise perspective, these agents would be like extremely savvy “cloud cost optimizers” – CFOs for compute spend. Companies could task algorithms to continuously arbitrage between providers and contracts. Perhaps an AI system will evaluate the forward curve of GPU futures (like those Ornn is creating) and decide to lock in 70% of next quarter’s needs at a fixed price, while leaving 30% to spot because it predicts new hardware, or more supply coming online might push prices down. All of this would be done in seconds by software negotiating with other software on exchanges. It’s a world where compute flows like money, guided by market forces with minimal human intervention.

Of course, such a future raises new questions. How do we express our “utility function” to such agents in a safe way? Will marketplaces be open and interoperable enough for agents to move freely, or will there be gatekeepers? Could this lead to hyper-efficient usage of global compute, or conversely might it cause instability (flash crashes in compute price due to algorithmic trading of GPU hours)? These are open questions, but they hint at just how transformative a commoditized compute market could be.

Conclusion

Semi-fungible asset markets are an exciting frontier where financial engineering meets real-world constraints. Our work on market clearing mechanisms, inspired by the paper “Market Clearing with Semi-Fungible Assets” is a step toward unlocking smoother trading in these complex markets - from bonds to compute and beyond. We’re excited about the potential: when buyers can treat almost-fungible items more flexibly, markets get more efficient and inclusive. Anagram is actively building in the semi-fungible space; if you’re as intrigued as we are and happen to be building something in this vein – whether it’s for cloud compute or any other semi-fungible resource – we’d love to hear from you.

About Anagram

Anagram is a modern institution for a novel technology. We're a team of 20 engineers and operators building companies that reshape how the world interacts with blockchain technology. We invest in people and work alongside them to accomplish their life's work.

Interested in building alongside us? Get in touch: info@anagram.xyz

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

The information in this article has been prepared by Anagram Ltd. (“Anagram”) for educational and informational purposes only. Under no circumstances should this, or any post on this website, be construed as solicitation for investment in Anagram, its affiliates, or any projects named herein or otherwise. The contents herein, and content available on any associated distribution platforms, including Anagram online social media accounts, should not be construed as or relied upon as investment, legal, tax, or other advice.

Certain information contained herein, including in charts and graphics, may have been obtained from third parties. While such sources are believed to be reliable, Anagram does not assume any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of such information. No assurance is made by Anagram regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions set forth herein, whether or not obtained from third parties, and Anagram shall not be liable therefor. Certain statements herein are based on subjective beliefs, may differ from the views of other market participants, and are subject to change.

This presentation contains “forward-looking statements,” which can be identified by the use of forward-looking terminology such as “may”, “will”, “should”, “expect”, “anticipate”, “project”, “estimate”, “intend”, “continue” or “believe” or the negatives thereof or other variations thereon or comparable terminology. Due to various risks and uncertainties, actual events or results may differ materially and adversely from those reflected or contemplated in the forward-looking statements.

Anagram and its affiliates may consult, invest, build, or otherwise have interest in companies or projects that are written about in this space. This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute advice, marketing or solicitation for funding.